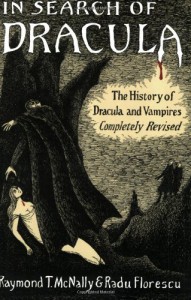

A very fascinating book for fans of Dracula, esp. if you are interested in the history behind the real figure (Vlad Tepes), locations, etc.... Part history, part folklore, part opinion, this book has a nice variety of information.

A very fascinating book for fans of Dracula, esp. if you are interested in the history behind the real figure (Vlad Tepes), locations, etc.... Part history, part folklore, part opinion, this book has a nice variety of information.In addition to the historical sections about Romania & the Dracula family, I also enjoyed the section on Bram Stoker, his research, & other books that have been variations on the Dracula/vampire legends. The film section was fine (but I haven't seen any of the films mentioned, so it wasn't entirely applicable to me).

That said, between the sections on the mass murders & extreme cruelty of Vlad Tepes and Elizabeth Bathory, real life is much scarier & horrific than fiction. Dracula, the vampire character, seems tame in comparison to these blood-thirsty sadists of history. There is definitely some disturbing information in this book.

The extensive bibliography is wonderful. I do wish there had been more/better maps.

Overall, highly-recommended for Dracula fans.

----------------

(Earlier comments while I was reading the book...)

Still in progress, but I'm finding this to be a bizarre, creepy, & riveting history book.

For those interested in some of the history of Dracula (the real, historical person, not the vampire), a few quotes from [b:In Search of Dracula: The History of Dracula and Vampires|37722|In Search of Dracula The History of Dracula and Vampires|Radu Florescu|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1348751452s/37722.jpg|37540]...

"The names of Dracula and his father, Dracul, are of such importance in this story that they require a precise explanation. Both father and son had the given name Vlad. The names Dracul and Dracula and variations thereof in different languages (such as Dracole, Draculya, Dracol, Draculea, Draculios, Draculia, Tracol) are really nicknames. What's more, both nicknames had two meanings. Dracul meant "devil," as it still does in Romanian today; in addition it meant "dragon." In 1431, the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund invested Vlad the father with the Order of the Dragon, a semimonastic, semi-military organization dedicated to fighting the Turkish infidels. Dracul in the sense of dragon stems from this. It also seems probable that when the simple, superstitious peasants saw Vlad the father bearing the standard with the dragon symbol they interpreted it as a sign that he was in league with the devil."

(Again, referring to the historical figure of Dracula...)

"The progressive popularization of the Dracula story, however, was due to the coincidence of the invention of the printing press in the second half of the fifteenth century and the production of cheap rag paper. The first Dracula news sheet destined for the public at large was printed in 1463 in either Vienna or Wiener Neustadt. Later, money-hungry printers saw commercial possibilities in such sensational stories and continued printing them for profit. This confirms the fact that the horror genre conformed to the tastes of the fifteenth-century reading public as much as it does today. We suspect that Dracula narratives became bestsellers in the late fifteenth century, some of the first pamphlets with a nonreligious theme. One example of the many unsavory but catchy titles is: The Frightening and Truly Extraordinary Story of a Wicked Blood-thirsty Tyrant Called Prince Dracula.

No fewer than thirteen different fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Dracula stories have been discovered thus far in the various German states within the former empire. Printed in Nuremberg, Lubeck, Bamberg, Augsburg, Strasbourg, Hamburg, etc., many of them exist in several editions."

And, just as I was thinking the same thing, the authors state...

"The deeds attributed to Dracula in the German narratives are so appalling that the activities of Stoker's bloodsucking character seem tame by comparison."

Indeed. I believe that may be an understatement.

And, on an interesting side note, I saw this portrait (Petrus Gonsalvus) & two of his "wolf children" in the book:

Wondering why this portrait would be in a book about Dracula?...

"Ironically, the only existing life-size portrait of Dracula is at Castle Ambras near Innsbruck. Ferdinand II, Archduke of the Tyrol, who owned Castle Ambras during the sixteenth century, had a perverse hobby of documenting the villains and deformed personalities of history. He sent emissaries all over Europe to collect their portraits and reserved a special room in the castle for displaying them. It made no difference whether the subjects were well known or comparatively obscure. What did matter was that they were actual human beings, not fictional ones. If such persons could be found alive, the archduke tried to settle them, at least temporarily, at his court, where paintings could be made of them on the spot. A few giants, a notorious dwarf, and the wolfman from the Canary Islands stayed on at Castle Ambras for some years. Dracula was already dead by the time this degenerate Hapsburg began his hobby, but the prince's reputation as a mass murderer was already largely established in the Germanic world because of the tales told by the Saxons of Transylvania. We do not know how or where Ferdinand's portrait of Dracula was painted or who the artist was."